Wildfire worries force evacuation of West LA VA housing and homeless shelters

Unhoused vets wonder how thousands of newly displaced people — including fellow veterans — will complicate their decades-long struggle for housing and supportive services on the 388-acre campus.

An extraordinary evacuation of veterans living on the VA’s West Los Angeles campus in the path of the Palisades fire is underway, raising new questions about efforts to solve Southern California’s decades-old veteran homelessness scourge.

Early Saturday, the VA and volunteers moved as many as 200 veterans to an American Red Cross shelter at Pan Pacific Park in the city’s Fairfax District and nearby Stoner Park Recreation Center in West LA. Then on Sunday evening, the unhoused service members were relocated to Bob Hope Patriotic Hall in downtown Los Angeles.

Several veterans at the shelters report they were grateful to escape the Palisades fire, which was spewing smoke and flames on a Santa Monica Mountain ridge above the VA’s 388-acre campus where they had been living in temporary and permanent housing. Ash rained like snow on the grounds where rats and coyotes had become emboldened to run in the open and in parts of neighboring Brentwood under an evacuation order.

In a statement Monday, the VA said it will continue to monitor the fires and take additional safety measures if necessary. Forecasts for early Tuesday call for a return of turbulent winds that many fear will propel the fire again.

Several sheltered veterans say their hearts go out to people who lost homes, property, and in some cases family members in the week-old firestorm. But they also worry that thousands of newly displaced people — including fellow veterans — will complicate their years-long struggle for housing and services. Latest estimates say 12,000 structures had been decimated in the firestorm.

Prior to being displaced by the evacuation, most of the veteran refugees were living in temporary housing on the VA campus; permanent apartments have rolled out very slowly under a 2015 court settlement over the past decade. In a class-action lawsuit filed against the VA decided in September 2024, a federal judge sided with unhoused veterans suing for housing on the 388-campus, and ordered the government to build 100 units of modular housing by February 2025. The VA appealed the ruling in October, halting construction and preparation of the temporary housing.

Get the whole story: An epic government scandal hiding in plain sight

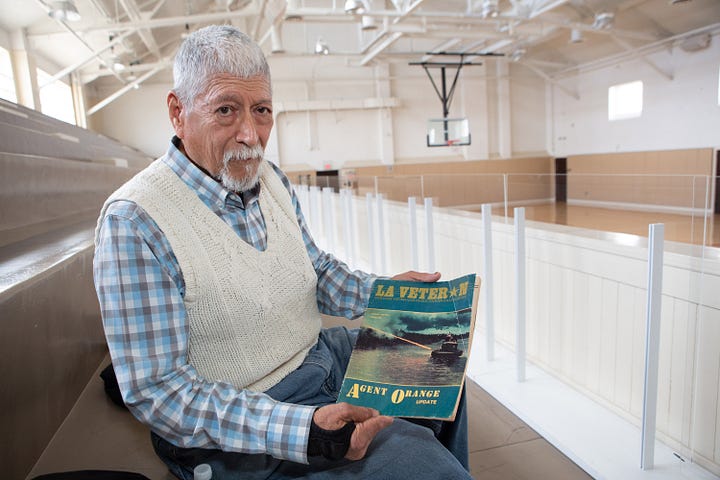

Home of the Brave is a newsletter and an award-winning, multimedia feature documenting the unhoused veteran crisis at the West LA VA campus, a 388-acre property deeded to the U.S. government in 1888 specifically to house disabled soldiers. Over the last 50 years, the land was carved up and leased to private interests, while development for veteran housing has been painfully slow. A land grab dating back to the U.S. Civil War, the history of this land is a story bursting with government malfeasance, neglect, graft, and even death.

This newsletter reports on how veterans are fighting to reclaim the land through Powers v. McDonough, a class-action lawsuit filed against the Department of Veterans Affairs. Get updates on the case here:

Navy veteran Jack Baker, 47, says he was struck when a service employee at a Red Cross shelter where he was moved Saturday remarked, “These clients didn’t lose everything.” People seem to lose sight that previously unhoused veterans have lost everything, including, in some cases, their mental and physical health, Baker says. They have spent decades recovering after the country failed to keep its promise to care for them, he adds.

“The best case scenario is the [newly displaced] won’t have to go through all of the hoops and disconnects we’ve had,” Baker says. “But now are we going to have an express lane for those recently displaced?”

Baker notes that people aren’t even using the same words for the fire refugees and homeless veterans. “The new people who lost their homes are ‘displaced,’” he says. “Well there already was a whole group of people who were ‘unhoused.’”

The VA evacuation began early Saturday “in an abundance of caution,” the agency said in a statement, and included residents of the CTRS tiny homes, the Bridge Home congregant tent shelter, the assisted living center, and veteran apartments on the north side of the massive property. Campus developers Thomas Safran Associates and US Vets conducted a voluntary evacuation Saturday afternoon, veteran and advocate Rob Reynolds confirms.

The VA did not disclose how many residents were moved. The latest campus bed count posted to the VA’s Master Plan website notes availability for 757 veterans across its permanent, transitional, temporary, and emergency housing, but that information is only current as of August.

Tightly spaced rows of cots, each covered with a white blanket emblazoned with the Red Cross’ red and blue logo, sat mostly empty at Pan Pacific Sunday afternoon as veterans played dominos, watched football on their phones, and ate lunch outdoors in the hot midday sun. Food was brought in from the campus for meals.

CTRS residents said they were pulled out of their tiny houses early Saturday and ordered to board buses without being told where they were going or for how long. Residents of the Bridge Home tent — which some veterans call “the biodome” — said the shelter was an improvement on their current quarters. “We’ve been living on disaster relief since I got here — this is better,” says Dave Hart, a retired Navy veteran from Baltimore who came to the West LA VA for medical care.

Some veterans from the West LA VA’s CTRS tiny shelters — where they live in sparse, private units the size of a shed — couldn’t handle the crowded shelter setting and had already returned to street homelessness or were looking for hotel rooms, Reynolds says.

Reached by phone, veteran Chris Trainor says he walked from Pan Pacific back to the West LA VA medical center, where he watched other veterans trickle in by twos and threes Sunday afternoon as he tried to get a motel room.

The long-term concern, Reynolds says, is that veterans’ will disappear or fall out of the lengthy process for securing housing from the VA. If the VA had complied with US District Judge David O. Carter’s October order to stand up modular housing quickly, veterans could have been moved out of danger to the south side of campus with much less disruption, Reynolds says.

In September, Carter ruled the VA had breached its fiduciary duty to house veterans and ordered thousands of new permanent and temporary housing units to go up across the campus, including the north side, where veterans currently live, and the south side where they do not. The judge spent weeks with development experts and lawyers hammering out procurement and installation of 100 modular housing units by February 1. The VA appealed Carter’s judgment in October, putting the modular plan on hold. A federal appeals court hearing is set for April.

A court ordered the VA to build housing for homeless vets. Here’s the plan it’s fighting to block

Winter rains are coming to Los Angeles County, where more than 3,000 unhoused veterans live on the streets. As a part of a landmark judgment that excoriated the VA for decades of mismanagement of its West Los Angel…

Reynolds says he expects homelessness among veterans to soar with the fire dislocation. He has already fielded reports of veterans and VA employees losing their homes, mostly in the second largest blaze, the Eaton fire in Altadena. “The homeless numbers are now unreliable,” Reynolds says. “Homelessness is going to significantly increase.”

Even before the fires, the VA had been turning away veterans seeking emergency shelter on the West LA campus. At an oversight meeting in December, the VA, which had long insisted its emergency housing resources were adequate, acknowledged veterans were unable to find emergency shelter on campus because of demand from the cold weather and “capacity issues.” But the agency said it has adequate space at other locations.

Veterans outside the Pan Pacific Recreation Center Sunday say the only off-campus shelter the VA offered them was on Skid Row or in sordid and filthy facilities. “I was on Skid Row — I lasted a week," says Michael Edwards, a Navy veteran. “I wanted to grab people by the throat.”

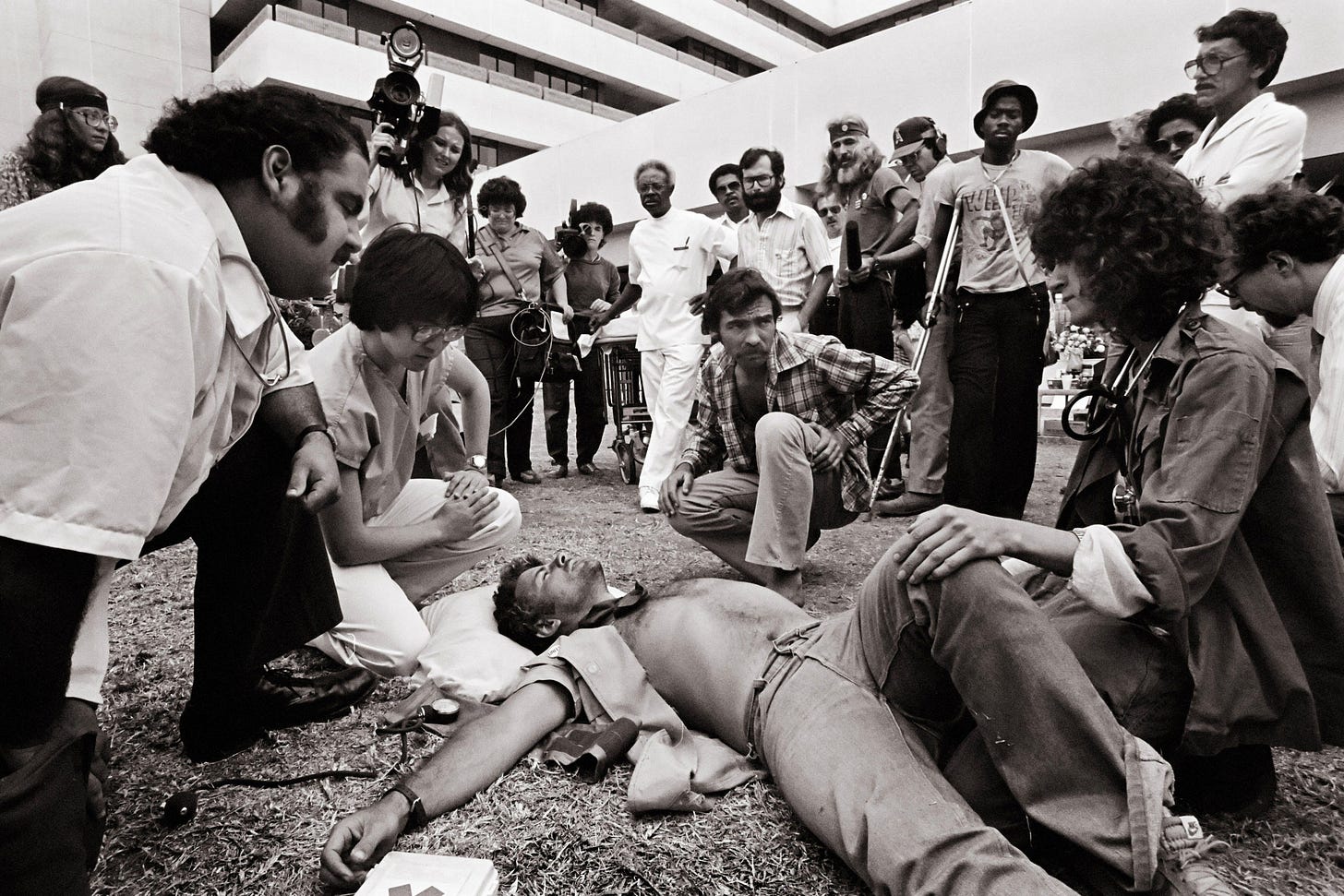

A 50-year battle for housing

At its peak in the late 1950s, the West LA VA campus housed around 5,000 veterans. Then, after a deadly 1971 earthquake and a flood of broken promises, the government ordered veterans living on the campus to vacate within a month. For the past 50 years, Los Angeles veterans have been fighting their own government in a battle for housing that’s still raging today. Learn more by reading Part Three of Home of the Brave: “The Land War.”

A number of evacuated veterans were over 60, and several were recovering from serious health problems, including June Gentry, 82, an Air Force veteran who broke his hip and moved into a campus tiny home while he gains strength to walk again. Housing in a safe environment close to medical treatment is critical to his healing, he says.

Baker questions whether veterans had been moved to the Bob Hope Patriotic Hall on Sunday evening because of objections from Pan Pacific neighbors whose children played on swings and slides next to veterans in wheelchairs and mobility chairs, smoking and cursing. “The community was not ready to have vets there,” Baker says. ”The unspoken thing was, ‘They gotta go.’” The veterans are expected to remain at Patriotic Hall through Tuesday.

A trained Harley-Davidson mechanic, Baker says a job injury, divorce, and child support payments triggered his homelessness. It took him five years of legal action and appeals while he lived in his car and worked at various sales jobs to get a housing voucher from the VA. He has been told he will move into an apartment on the West LA VA campus any day.

“The VA was charged with keeping America’s promise to the people who did the most noble thing they could do,” Baker says. “Then they were left out like trash.”

Long Lead’s regular coverage of Powers v. McDonough will continue soon. Opening briefs due to the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals Friday, January 17.