A court ordered the VA to build housing for homeless vets. Here’s the plan it’s fighting to block

A virtual tour of the modular housing villages proposed for the VA's massive, 388-acre West LA campus

Winter rains are coming to Los Angeles County, where more than 3,000 unhoused veterans live on the streets. As a part of a landmark judgment that excoriated the VA for decades of mismanagement of its West Los Angeles campus, U.S. District Judge David O. Carter ordered the agency to procure and install 100 temporary housing units in October, to get ahead of the weather.

On a recent morning, development experts and VA employees met outside UCLA’s Jackie Robinson stadium to review site preparations to bring emergency housing to the campus. The experts, including Steve Soboroff, who oversaw the Playa Vista development on LA’s Westside, are working for veterans who sued the VA over its failure to house homeless and disabled veterans.

The experts have identified three sites where 106 high-quality, one-bedroom modular units — with kitchenettes, full baths and living rooms — can go in before the brunt of the storms. Clustered around landscaped courtyards, the homes will form tiny villages, making good on the VA’s long-delayed promise to turn the property into a thriving veterans community, the experts say.

Long Lead has been reporting from Powers v. McDonough every day court has been in session, and we will continue to follow this issue in this newsletter. Subscribe here to get updates sent direct to your inbox as soon as they publish:

But days before the site meeting, the agency went to court to appeal Carter’s ruling — as well as his emergency order mandating the temporary housing — for the VA to produce thousands of temporary and permanent housing units.

In a statement, the VA said it was committed to housing homeless veterans, but Carter’s ruling would divert resources from vital veteran services. Carter is asking the VA to pay the cost of the modular communities, preliminarily estimated at $15 million, a pittance of the agency’s $324 billion budget.

Prior to the appeal, lawyers and local VA staff had cooperated over weeks of court hearings and meetings to develop the modular project, but federal officials in Washington included it in their appeal. The legal fight could take years, but Carter has ordered preparations, including the site visit, to continue.

The West LA VA campus was deeded after the Civil War as a home for old soldiers, and served thousands of veterans until the 1970s, when the VA pulled out of housing. As homeless veterans slept outside in bushes and tents, the VA allowed neglected buildings to deteriorate while officials issued valuable land leases for UCLA‘s baseball stadium, the Brentwood School’s athletic facilities, oil and gas drilling, and other commercial interests. Carter, in his ruling, voided these non-“veteran-centric” leases, but the VA wants to negotiate new deals with UCLA and Brentwood.

After a previous lawsuit, the VA made a deal with a non-profit development consortium to create 1,200 units of permanent supportive housing units with conventional financing. But nearly 10 years later, only 307 units have opened, 70 of them very recently. The campus also has tent and tiny home shelters for about 160 veterans and partners.

“At this rate, it will be another 50 years before the housing goal is reached,” Soboroff said in an interview.

Today the West LA VA has a “Grey Gardens” vibe. Its once-iconic chapel is in ruins and barracks-style buildings are dilapidated. A Japanese garden tucked away in the back of the campus is closed, and internal roads lead nowhere.

The property also is graced with rolling greens and glens. The modular housing would provide some of the “connective tissue” to the rest of the campus it lacks, Soboroff said.

“If something is landscaped really well, it’s good for mental health — as opposed to something that looks like an internment camp,” said veteran advocate Rob Reynolds.

The 350-to-400-square foot units resemble single-family homes, with porches, pine walls, and wood-like vinyl flooring planks. The homey touches could help veterans adjust to civilian life and cost not much more than building a shelter experts say.

Each modular unit would come with a microwave, dining table and chairs, couch, refrigerator, fire sprinklers, mini-split electric heat pump and air conditioning, and a proper bedroom and bathroom, veterans expert Randy Johnson, a longtime development executive said. Small staircases lead up to the front porch.

Carter vetoed cooking facilities because of a fire risk, but they could be added later. In the meantime, the VA will provide a chow wagon and laundry facilities.

Planter boxes can be brought in to landscape courtyards, where veterans could read a book, play cards, or socialize, said Gensler architect Kelly Farrell, who is on the experts’ team.

During a court hearing last week, VA lawyer Brad Rosenberg argued to reduce the square footage and eliminate the porches so more units could be crammed in. Johnson said the units’ ramps use the porches as landings, and reductions would yield very few additional units, at a cost to liveability and dignity for the veterans.

“We want people to be able to have all the emotional and well-being benefits that come with a home,” Farrell said.

“Why are we solving this to the bare minimum of shelter?” Soboroff said. “Let’s do something respectful that heals people quicker.”

The modular units could also fill holes in the VA’s shelter system, said Rob Reynolds, an Army combat veteran and advocate. Low-barrier shelters like the Care, Treatment and Rehabilitative Services (CTRS) site — a group of approximately 135 tiny shelters on the West LA VA campus — are vital to get veterans struggling with substance abuse and mental health disorders off the streets. According to Reynolds, VA changed its policy in April 2024 to shorten CTRS stays, requiring vets to be engaged in a housing plan within 60-to-90 days. If the veteran preferred to live in on-campus housing at the West LA campus and none was available, they would have to accept off-campus housing, or leave the tiny shelters.

But these modular homes could help veterans stay on the campus, Reynold says, temporarily and with access to supportive services, until the permanent housing is constructed. Veterans who are in recovery or have found employment, for example, may find support while grouped into these temporary, modular communities with vets in similar situations, as they wait for the permanent campus housing to open.

Eventually, the experts would like to see modular villages adapted for different populations: disabled veterans near treatment at the medical center, veterans in recovery in sober living, and women with children in a family setting. Soboroff said veteran students and VA employees who have to drive in from San Bernardino for their medical treatment at the LA facility could be housed. The modular units could be converted for permanent housing.

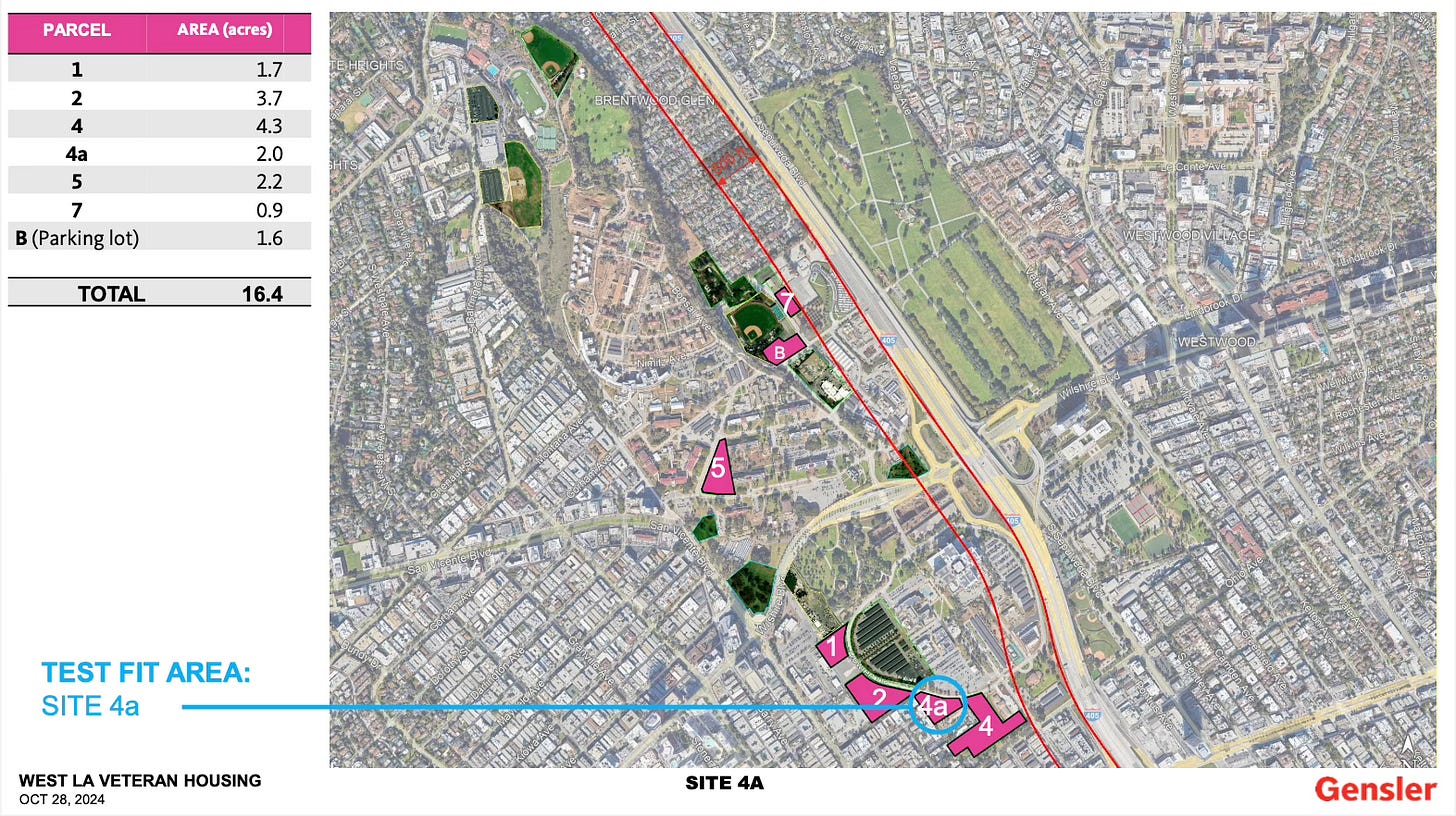

The first three housing sites are all on paved parking lots, which are easier to build on than raw land. The stadium lot (identified as “B” in the map above) is on the north campus, in view of a tree nursery with lines of Canary palms and ash trees.

That site curved in a horseshoe shape near the second site (identified as “7” in the map above), by the Columbarium, where veterans’ cremated remains are interred in a park-like setting.

“You look out, you see a tree,” said Johnson.

The third site (identified as “4a” in the map above) sits on the edge of parking for the medical center, across Wilshire Boulevard on the south campus. During the site visit, VA officials said utility hookups at the first two sites were doable, but problematic on the south campus, where the housing could interfere with staging and contractor parking for the upcoming construction of the $1.5 billion critical care center and research building.

Soboroff said they can work around the construction, and in court, Carter made it clear he would bridge no obstacles. “I expect to hear a parade of horribles about any site.” the judge said.

Carter set a hearing Thursday on the VA’s request for a stay on his order until the appeal is finalized. Veteran experts hope to learn whether the VA will continue to let them work on campus in case the decision breaks their way.

Homeless veterans shouldn’t have to wait any longer for housing, Soboroff said. “It’s as big an emergency as a hurricane, flood or fire,” he said.

“There is no reason we can’t have this housing,” Johnson said. “The veterans deserve it, period.”

The next hearing is scheduled for Thursday, Nov. 7 at 11:00 a.m.