Day 2: Reynolds testifies on the VA's treatment of unhoused LA vets

“We had veterans in wheelchairs and walkers that were physically unable to get down on their hands and knees and crawl into the tent,” he said in his second day of testimony.

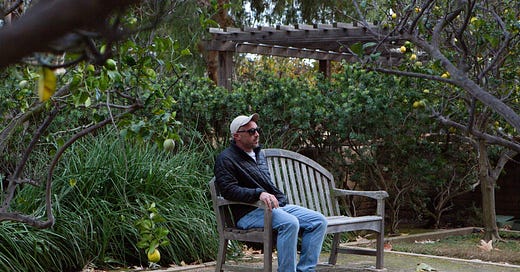

Rob Reynolds’ journey to a federal courtroom began with him taking pictures of military veterans sleeping on a busy Los Angeles boulevard.

It was during the pandemic, and the Iraq war veteran couldn’t understand why so many of his fellow veterans were sleeping outside on San Vicente Boulevard. Their homelessness bothered him so much he photographed some sleeping and photographed sheriff’s deputies “coming through one time and clearing their stuff away.”

He placed the photos on a poster and took it to a meeting of the Veterans Community Oversight Engagement Board (VCOEB).

“I just couldn't understand why these veterans were sleeping on the street,” Reynolds testified Wednesday in a federal bench trial in Los Angeles federal court. “I had no idea, really, about the land at that time.”

Reynolds said he asked the VCOEB why all the veterans were out there. After the meeting, fellow veterans approached and told him about a years-old court case and longstanding allegations that the massive veterans hospital property in West LA “is being illegally leased and the VA is not taking care of veterans.”

“And it was just infuriating to think that something like that could happen,” Reynolds said.

Reynolds returned to the witness stand Wednesday morning after testifying Tuesday about the horrors he experienced in Iraq and the problems he experienced when he returned home. His testimony Wednesday focused on his path from troubled veteran to impassioned advocate with AMVETS. The trial before U.S. District Judge David O. Carter, a U.S. Marine veteran who has a Purple Heart and Bronze Star from the Vietnam War, is to help Carter decide how to proceed after issuing two major orders that say the U.S. Veterans Administration discriminates against veterans who are homeless and eligible for housing built on the VA’s west LA campus because of their disability compensation. The judge said the VA has a fiduciary duty to use its 388-acre campus for housing and health care. The VA currently leases some of the property for sports fields, parking, and oil drilling, among and other uses unrelated to serving veterans.

Reynold testified about learning of the complicated history of legal challenges to the land use, and realizing that he wasn’t alone in his anger.

“During this period of time, did you ever speak with a veteran who thought it was okay in terms of what had been done with respect to the deed?” asked plaintiffs’ lawyer Mark Rosenbaum of Public Counsel.

“No, I never did,” Reynolds testified. “Every veteran that I met was very upset by what was going on and wanted to do anything they could to help fix it.”

Reynold said he came to know the phrase “Veterans Row” to refer to “San Vicente Boulevard outside the gates of the West LA VA where veterans had been sleeping and dying for years waiting to get into the VA.”

Reynolds recalled attending a town hall meeting with other veterans in early 2020. He said a VA official conceded, “You know what? Maybe we haven't been doing things correctly out there, and we'd like to help.”

But what happened after that only seemed to be part of the problem.

The VA allowed veterans “to set up tents inside the VA,” but the VA didn’t provide them, the Brentwood School, which leases some of the campus property, did.

“I never went inside because they were too small to go inside,” Reynolds testified. “We had veterans in wheelchairs and walkers that were physically unable to get down on their hands and knees and crawl into the tent.”

“Was there room inside those tents for the belongings of those veterans?” Rosenbaum asked.

“No,” Reynolds answered.

There also weren’t real bathrooms, only portable toilets.

“The veterans with disabilities could hardly even stay in those tents because of how small they were,” Reynolds said.

Reynolds said another veteran “offered to donate large 10x14 tents to the VA for their new program they were creating, and the VA turned down those donations.”

“Over this period of time, did you observe any insects or rodents around the tents?” Rosenbaum asked.

“That was always an issue, yes,” Reynolds answered.

“Did the veterans talk to you about the rodents and the insects?” Rosenbaum asked.

“The big thing that they ever talked to me about is how they wanted to get into the VA or they wanted to stay on the VA, but they couldn't live in these child-sized pup tents,” Reynolds answered.

“At this period of time, Mr. Reynolds, was there any available permanent supportive housing on the VA grounds?” Rosenbaum asked.

“No, and there was none under construction,” Reynolds answered.

The Old Guard and the New Fight

Relentlessly protesting the lack of housing on the West Los Angeles VA campus, a group of vets sparked a battle over the land’s misuse. But after a contentious legal settlement ended the dispute and failed to deliver much-needed homes, a new generation of service members rose to continue their veteran revolution.

To learn more about how veterans from World War II to the present day led a tireless, 50-year campaign for housing, read Part 5 of “Home of the Brave,” now available from Long Lead.

Reynolds said he saw veterans get turned way from the VA hospital and have mental breakdowns on San Vicente Boulevard.

“I had veterans run out into traffic. I had veterans talk about wanting to commit suicide,” Reynolds testified.

Rosenbaum asked Reynolds if he believes the approach “was an adequate solution to veteran homelessness?”

“No, I think permanent, supportive housing is an adequate solution to their own homelessness,” Reynolds answered.

Reynolds recalled meeting with VA Secretary Denis Richard McDonough when he visited Los Angeles in 2021.

“He didn't answer me on the issues with the leases, but with the same-day shelter and permanent supportive housing. He said, ‘We’ll work on it,’” Reynolds said.

Reynolds also testified about sheds on the VA campus that currently house veterans.

“Do you know if there are veterans currently in those sheds who want to be in permanent supportive housing?” Rosenbaum asked.

“Yes,” Reynolds answered.

“How do you know that?” Rosenbaum asked.

“I speak with veterans, and I've never met a veteran that doesn't want to be in some type of permanent supportive housing or want something better for themselves,” he said.

Reynolds testified he believes the policy that classifies veterans disability compensation as income needs to change.

“There's no reason that that should deny them from getting into housing close to the hospital,” Reynolds testified.

Proceedings for Powers v. McDonough will continue on Thursday, August 8 at 8:30 a.m.