Shocking but true: 6 wild facts from LA's unhoused veteran crisis

Abraham Lincoln, Beverly Hills, and "Born on the Fourth of July" are all part of veterans' fight for housing at the West Los Angeles VA.

In 1888, wealthy landowners donated prime Los Angeles real estate to the U.S. government to house military veterans. Today the 388-acre property abuts the Brentwood neighborhood and the UCLA campus, is some of the country’s most valuable real estate, and houses very few vets — many in tiny, temporary shelters. Meanwhile, L.A. has become the homeless veteran capital of America.

Why isn't this land, which once housed thousands of disabled soldiers, home to more veterans? The answer is a scandal in plain sight, a story of government malfeasance, neglect, graft, and even death.

Home of the Brave tells the full story — from the property’s founding to the legal fight to take it back — of a centuries-spanning land war between the U.S. government, local forces, and generations of service members seeking a place to call home. Here are six wild facts from Long Lead’s recent feature on LA’s unhoused veteran crisis:

1. One of Abraham Lincoln’s last acts was establishing free housing for disabled soldiers.

One month before Lincoln’s assassination and the Confederate army’s surrender in the American Civil War in 1865, the president signed legislation establishing the National Asylum (later Home) for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers — a predecessor of today’s VA.

Amid the staggering rise of injured veterans, one facility became many, and eventually a network of at least a dozen soldiers homes formed nationwide, providing housing and services for those disabled by military conflict. Learn more about the property’s history here.

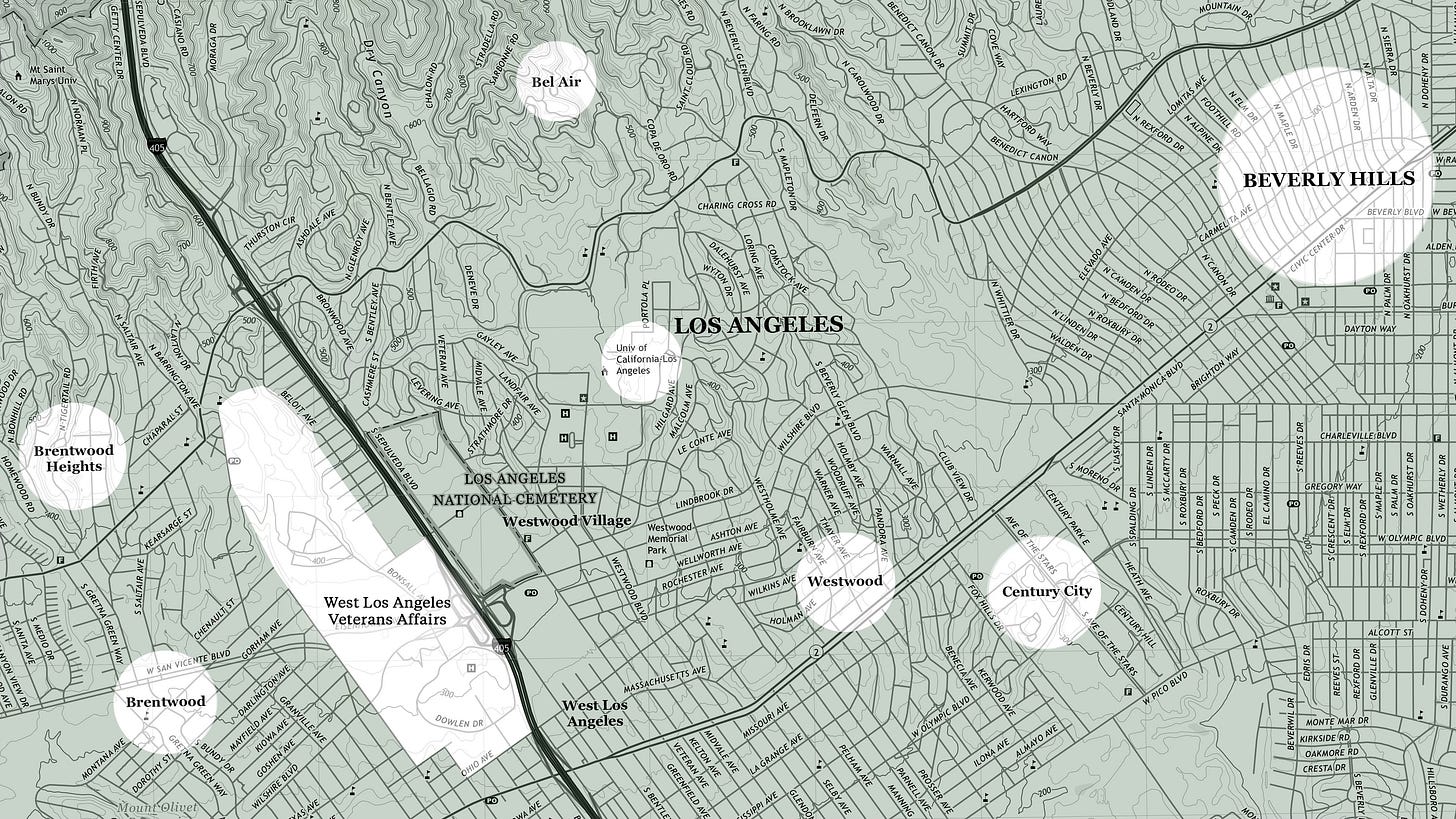

2. If not for the West LA VA, Brentwood, Bel Air, and Beverly Hills wouldn’t be worth what they are today.

In 1888, a powerful trio of landowners donated hundreds of acres of free land to the federal government to “locate, establish, construct, and permanently maintain” veteran housing in what was then called Sawtelle, now known as West LA. At the time, the Los Angeles Times praised the location, writing, “It will cause land in that section to advance in value, and the trade thrown into the way of our merchants will be considerable.”

Later, in 1912, property officials ceded some of the Soldiers Home land to Los Angeles County to extend San Vicente and Wilshire boulevards. A Times article noting the transfer stated that the “regal boulevards” were “bordered by the beautiful lawns, shrubbery and graveled walks bespeaking the true manorial homeplace.” Plainly stated, adjacent to the veterans’ property, Brentwood, “the perfection of suburban home places” (as the Times then described it), had arrived. Learn more here.

3. Ron Kovic, of “Born on the Fourth of July,” led hunger strikes protesting conditions at the West LA VA.

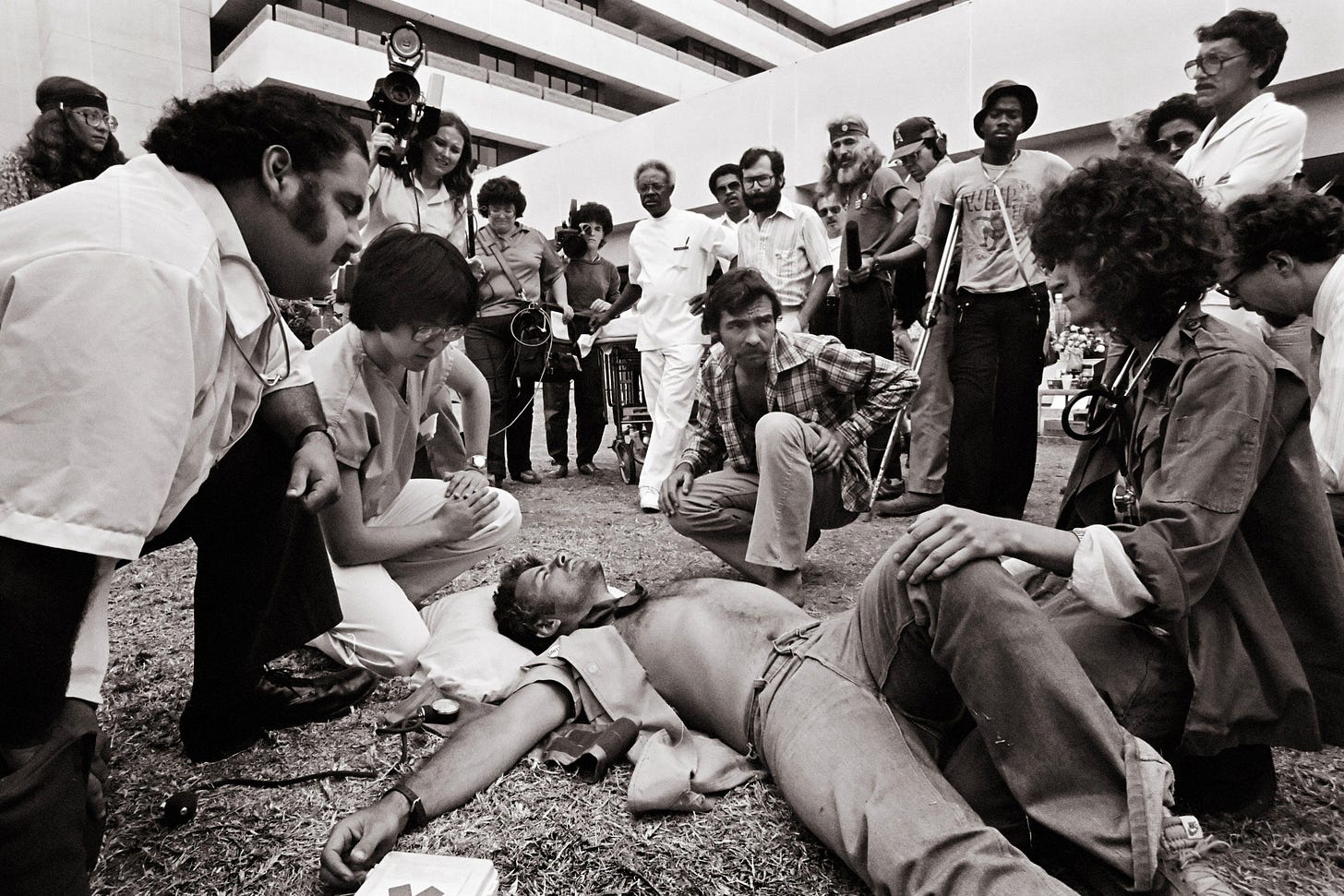

In 1974, around a dozen disabled vets, including Ron Kovic, author of the autobiography “Born on the Fourth of July,” (later turned into a film starring Tom Cruise) staged a hunger strike in LA, the first of several such protests over the next decade. Incensed by an array of mistreatment, the vets were demanding to meet with VA administrator Donald Johnson. Months later, Johnson was dismissed from his post by President Nixon, rather than face embarrassment at a Senate hearing on what its own administrators called the “medieval” Wadsworth Hospital, where patients “often die unattended in their own filth.”

The vets’ activism elicited national news coverage that highlighted the terrible impacts of conflict, as well as the government’s failure to heal war wounds. Discover how Vietnam veterans fought back against the VA.

4. The West LA VA had a parrot sanctuary, a Japanese garden, a university’s baseball stadium, an oil drilling operation, a golf course, a pair of theaters, and a private school’s athletic facilities.

Despite being home to all these varied entities, the campus now only provides permanent supportive housing for just 233 veterans. Read more about how the VA leased out the property instead of housing veterans on it in “Carving up the Map,” Part 4 of Home of the Brave.

5. 801 consecutive Sundays: That’s how long veterans protested in front of the VA to raise awareness of conditions on the campus.

The Old Veterans Guard, headed by Robert Rosebrock, protested for 801 consecutive Sundays at the corner of Wilshire and San Vicente boulevards, the site of the main gate of the West LA VA. Sometimes the protests consisted of just one vet; other times experienced demonstrators from the VA hunger strikes in the 1970s, like Kovic, showed up. But for more than 15 years of Sundays — rain, shine, or holiday — there was always someone standing on post there. Learn more about how these veterans fought for veterans housing here.

6. Veterans who are 100% disabled can be ineligible to live in new housing units at the West LA VA.

Though a group of disabled veterans are suing federal government for access to housing on the West LA VA campus, the judge has already issued a ruling that says the VA has discriminated against the vets.

But there’s an injustice that the lawsuit, which goes to trial on August 6, may not be able to address: The VA secured financing for West LA VA housing through the Department of Housing and Urban Development, which puts income restrictions on residents of its projects. However, veterans can receive disability payments for their service-related injuries, and the more severe a veteran's injury, the more money they’re likely to receive. As a result, vets who are 100% disabled can be barred from living in housing built for disabled veterans on the West LA VA campus.

Learn more by watching “The Promised Land,” Part 6 of Home of the Brave. An unflinching look at Los Angeles’s homeless veteran crisis, the documentary short by U.S. Army veteran Rebecca Murga, examines what life is like for the nation’s unhoused heroes whose government has left them behind.